Ice, Ice, Ice!

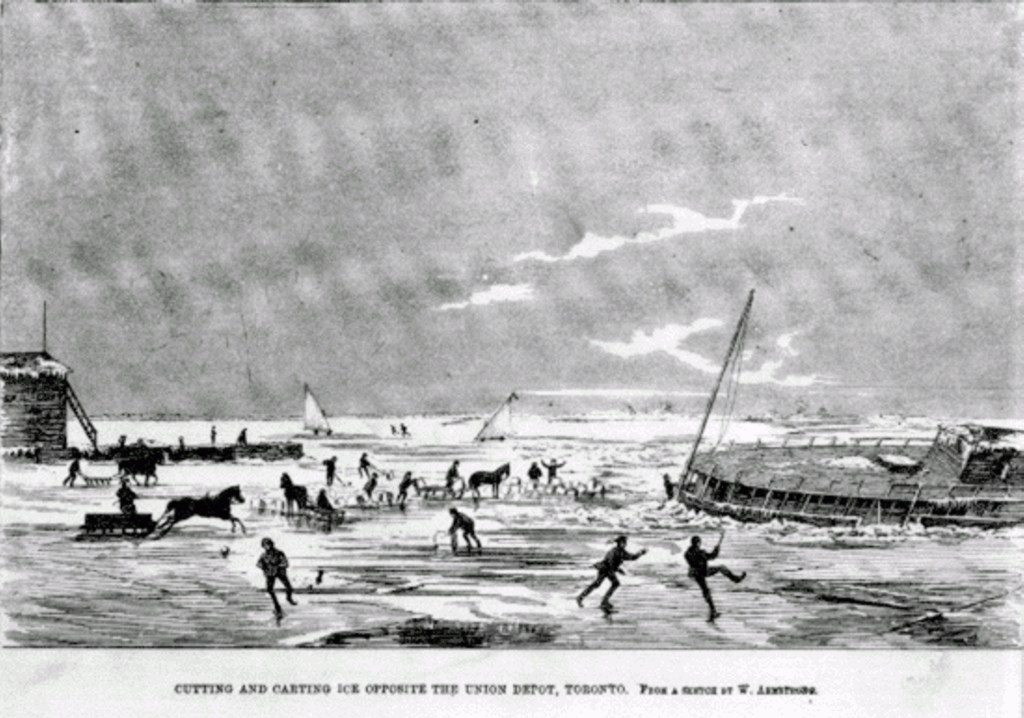

Settlers cut and sold ice from Lake Ontario, the bays, rivers, and ponds from the earliest days of colonization.

Waves of immigrants came into Ontario in the nineteenth century and entrepreneurs hired them to cut and haul ice, considered one of the most dangerous and low paying jobs of the time. For some it was a last resort, quick money when no other work could be found. For others, hard manual labour was their first Canadian work experience and a doorway to better things–whether it was working on the railways as porters, working in restaurants, cutting hair, and/or getting an education or opening their own businesses.

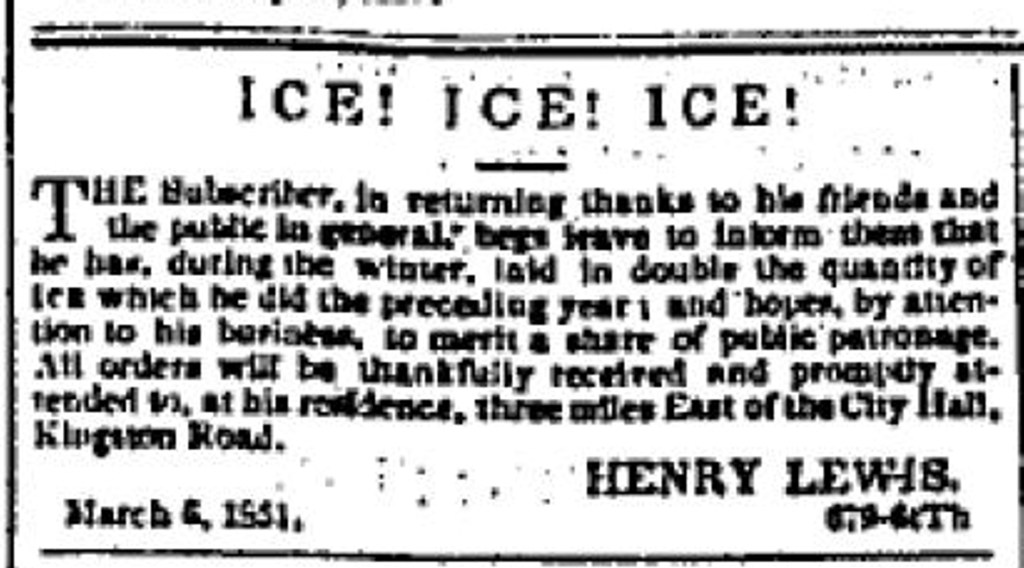

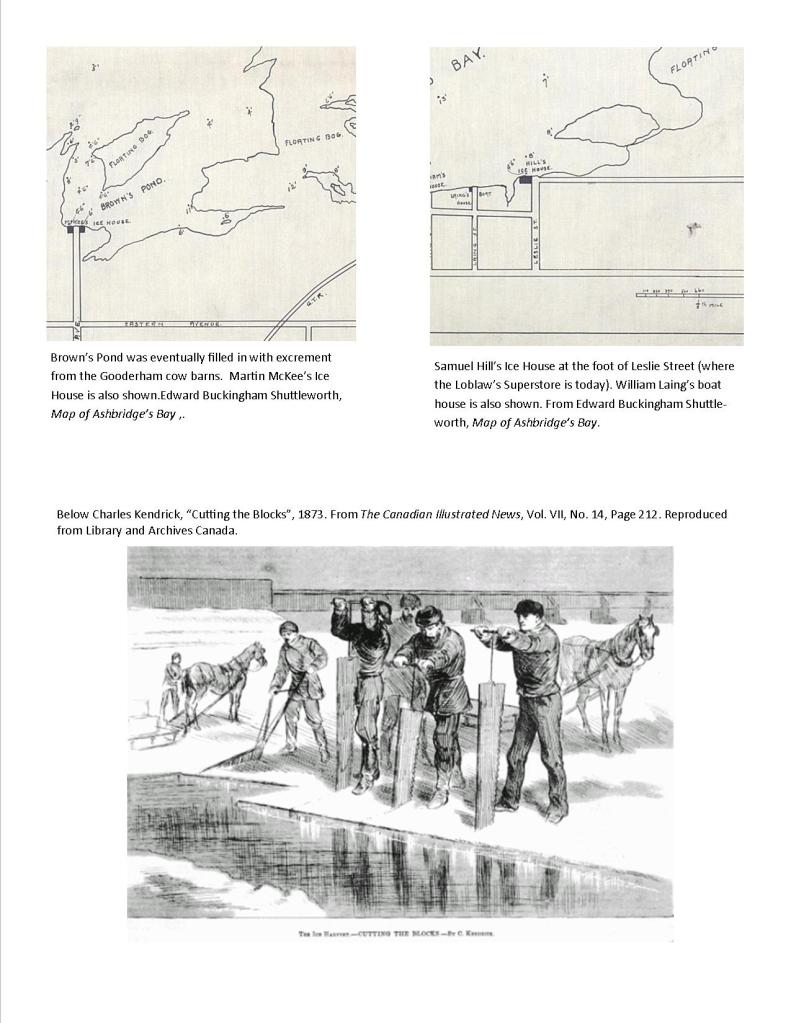

The Cary Brothers—George, Isaac, John, and Thomas—were African American entrepreneurs who arrived from Virginia in the 1830s and opened several barbershops in Toronto. In 1854, Thomas Cary and Richard B. Richards opened four ice houses, sourcing ice from Yorkville springs and Ashbridge’s Bay. Many of their workers were Black men who had escaped slavery.

Ice! Ice!! Ice!!! The Undersigned begs to return his best thanks to his customers, for the liberal patronage he has received for the last nine years, and to announce that he has enlarged and added to the number of his Ice Houses, having now four which are filled with pure and wholesome Spring Water Ice, from Yorkville. He is prepared to supply the same to consumers, by contract or otherwise, during the season, commencing from the 1st of June next. The Ice will be conveyed by waggon daily, to places within six miles of Toronto. All orders sent to Thomas F. Cary, hairdresser, Front Street, two doors from Church Street, will be punctually attended to. R.B. Richards, Toronto April 19, 1854.[1]

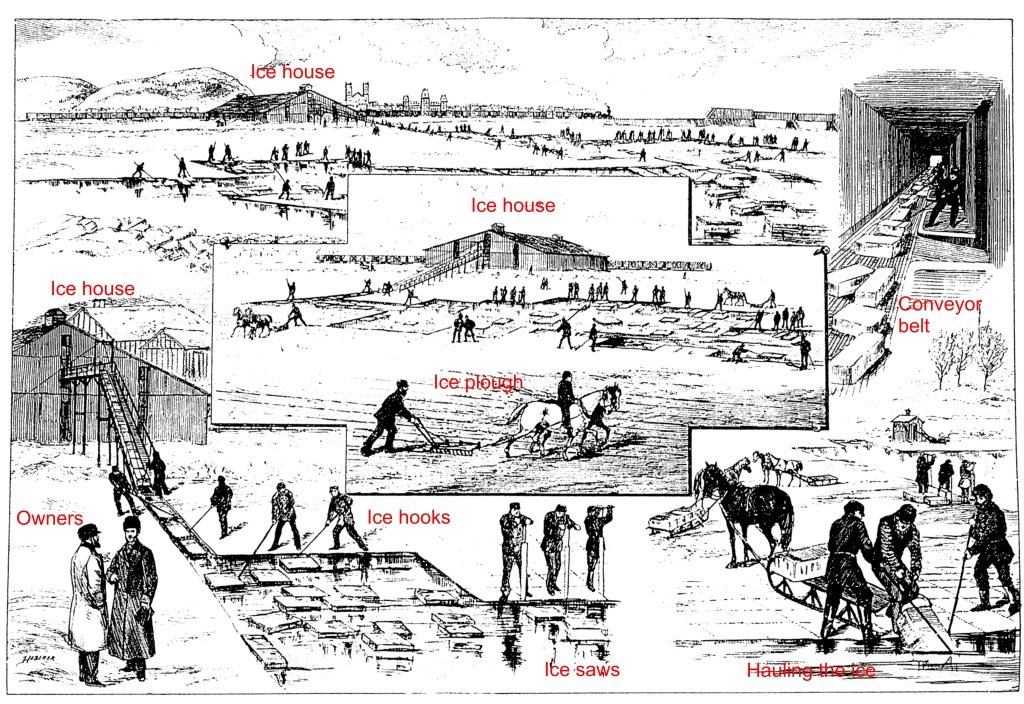

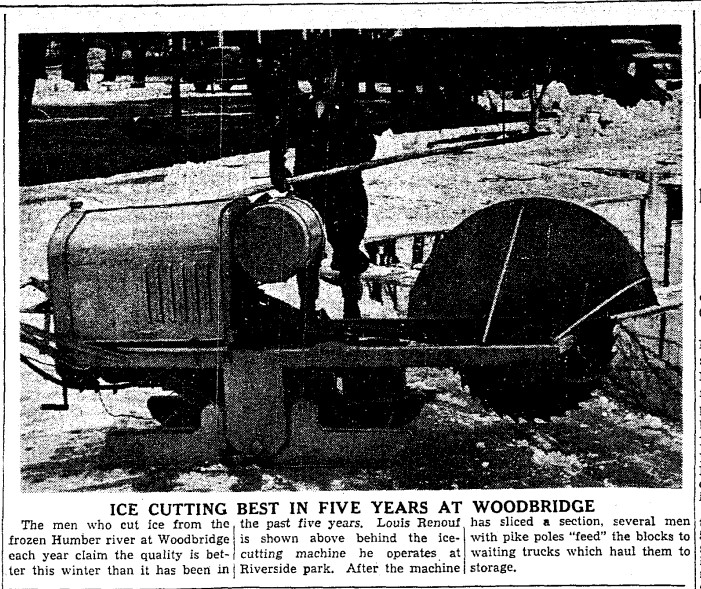

Ice cutting served as a crucial source of income in an era without unemployment insurance. The ice harvest commenced in January when the ice was sufficiently thick.

This ice was used in ice boxes to preserve food during the summer months and was transported by rail, even reaching destinations in the United States. Proximity to railway lines was imperative for ice houses:

Work went on night and day when the markets were most favourable and signs of an approaching thaw made their appearance. … As much as $1,200 to $1,500 profit were made off ponds an acre or two in extent. Every available railway car was brought into service for the conveyance of ice, and yet a sufficient number were not to be had to meet the demand.[2]

Poorer quality ice was used for refrigeration while cleaner ice was used for drinks and to make ice cream.

Ashbridge’s Bay and Toronto Harbour were very polluted by the 1880s. The area between the docks on the waterfront was thick with human excrement. Dirty ice helped cause the typhoid epidemics that ravaged Toronto in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But money trumped human health.

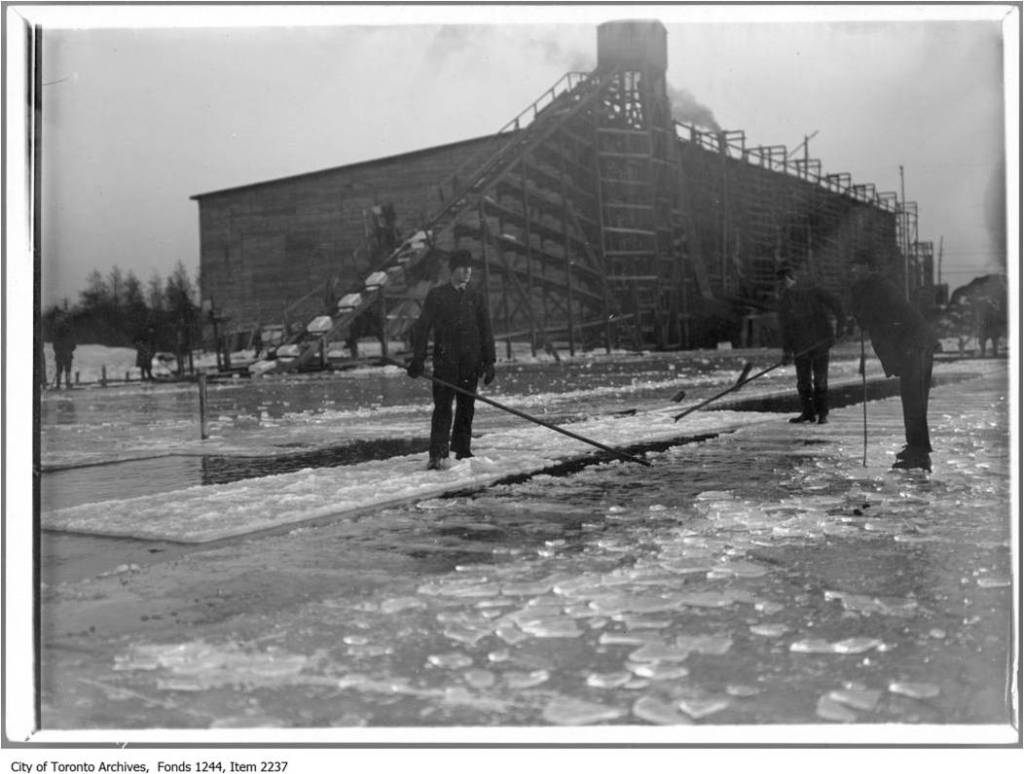

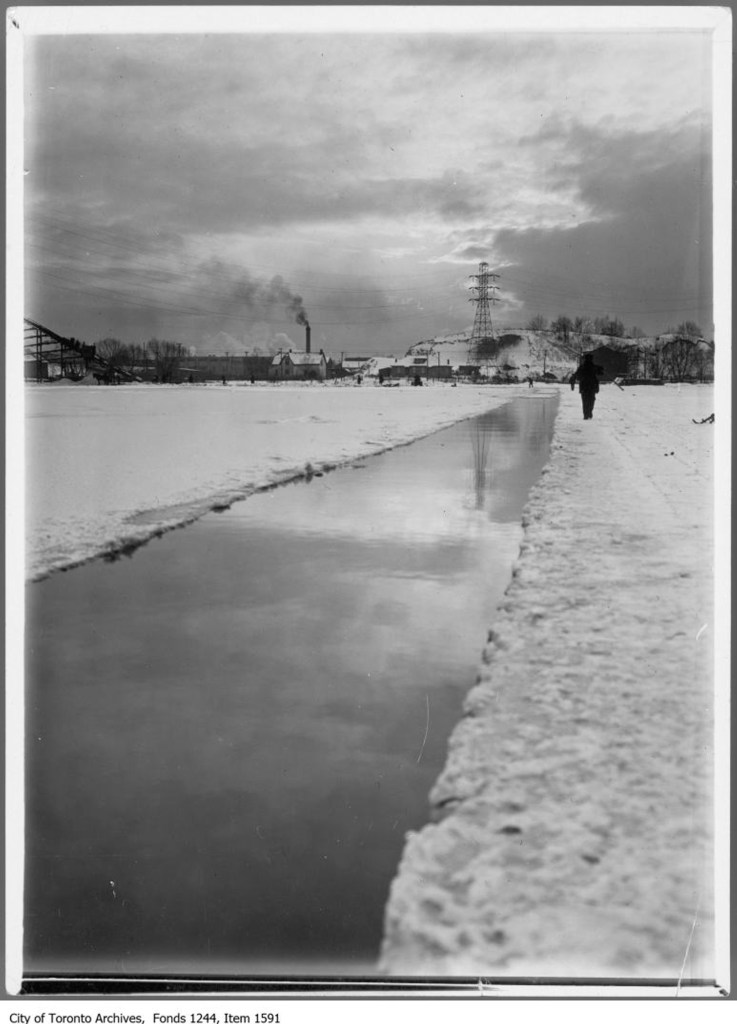

Men sawed the ice into blocks and packed it in sawdust in ice houses. Ice houses lined the north shore of Ashbridge’s Bay and other places along Toronto’s coast.

The icemen put evergreen trees and branches in the holes in the ice to mark it so that no one would stumble in and drown.

When the ice got to be six to eight inches, then the icemen appeared and several parties would commence the winter harvest. Great ice-houses in those days lined the bay at convenient spots for floating in the crystal blocks. This continued for several weeks, and was a busy time while it lasted. They generally saved all that the modest city required in those days, and it was not till the mild winter of 1880-81 that efforts were made to secure ice, outside, from Lake Simcoe, for the usual supply. Ice was cut, though, for many years afterwards till it was finally stopped by the city officials as being unfit for use. Up till then crowds of men and teams were kept busy in the operations of the ice harvest by the different companies engaged in that business. [3]

Ice cutting was profitable but low paying and dangerous. Horses and men often fell through the ice and drowned, and icemen sometimes succumbed to hypothermia in snow squalls.

William Booth, owner of Woodbine Ice Company, nearly drowned while walking on the Bay one Sunday, which some people saw as a lesson for working on the Sabbath.

Ashbridge’s Bay and Toronto Bay steadily became more polluted with sewage and excrement from the nearby cow barns and industrial pollution.

In 1882 an observer commented that:

It would seem as though many of the persons who have contracted for the principal ice-houses in the city have determined to take their material from the very foulest places…the concentrated essence of nastiness…”[4]

Despite its brown or yellow color and foul smell, the icemen insisted their ice was pure. Even as concerns about Toronto’s water quality grew, new ice houses were still being constructed and vast quantities of ice were shipped across Canada and to the United States, even as far as California.

There was danger both in the water and danger on the waters. The sandbars constantly shifted and what were safe shallows one day could become deep holes the next. Unpredictable currents, undertows and winds that riffled the surface water one moment, and blew up whitecaps the next made the ice treacherous.

There was a consensus that Toronto Harbour, Ashbridge’s Bay, Grenadier Pond, the Don River (especially the Don River), and other ice cutting sites required improvement due to their dirty and dangerous conditions. Either that or ice cutting would have to stop and ice be sourced from elsewhere.

When the Simcoes arrived in the early 1790s, Toronto Harbour was so clear that Elizabeth Posthuma Simcoe could see the bottom even far from shore.

John McPherson Ross, an employee of George Leslie at the Toronto Nurseries, described the clean body of water as he saw when he was a boy:

Ashbridge Bay…was a beautiful sheet of water when I first saw it in the summer of 1863, and was clean and good enough to drink, abounding in fish, and was the haunt of numerous wild fowl all summer. In the stormy, rainy fall, it was alive with wild ducks of all kinds that came to rest on their southern flight and to feed on plentiful masses of wild rice that grew in numerous patches. The marsh covered the shallow waters of the eastern part of the bay at the commencement of the sand bar by the foot of Woodbine avenue, as this roadway is now called. When the racetrack of that name was first built the marsh growth ended where the deep water started, and began again intermittently a little west of Leslie street. It was quite a fine sheet of water, and at the time of speaking the lake had made a cut at about the size of the present entrance.[5]

The issues began before Ross saw the Bay. In 1854, Sir Sandford Fleming commented on Toronto Harbour:

All the drains and sewers empty into the [Toronto] Bay, making it, in truth, the grand cesspool for a population of 30,000 inhabitants with their horses and cattle.[6]

The solution was to build a sewer main to dump Toronto’s waste into Ashbridge’s Bay. Engineers aimed to address sewage disposal and clean water supply without considering sewage treatment. They piped waste far into the bay and placed water intakes as far from it as possible, though not always far enough. People got sick from the ice in their drinks. Sewage treatment only later became a priority in Canada. But with time, the ice business shifted its operations north and away from Toronto.

[1] Globe, August 27, 1855.

[2] Globe, February 4, 1882.

[3] Globe, January 8, 1918.

[4] Toronto Daily Mail, December 12, 1882.

[5] Globe, January 8, 1918.

[6] Fuller, “Toronto Harbour”, The Canadian Engineer, Jan. 29, 1909.

Leave a comment