Ice transformed our world

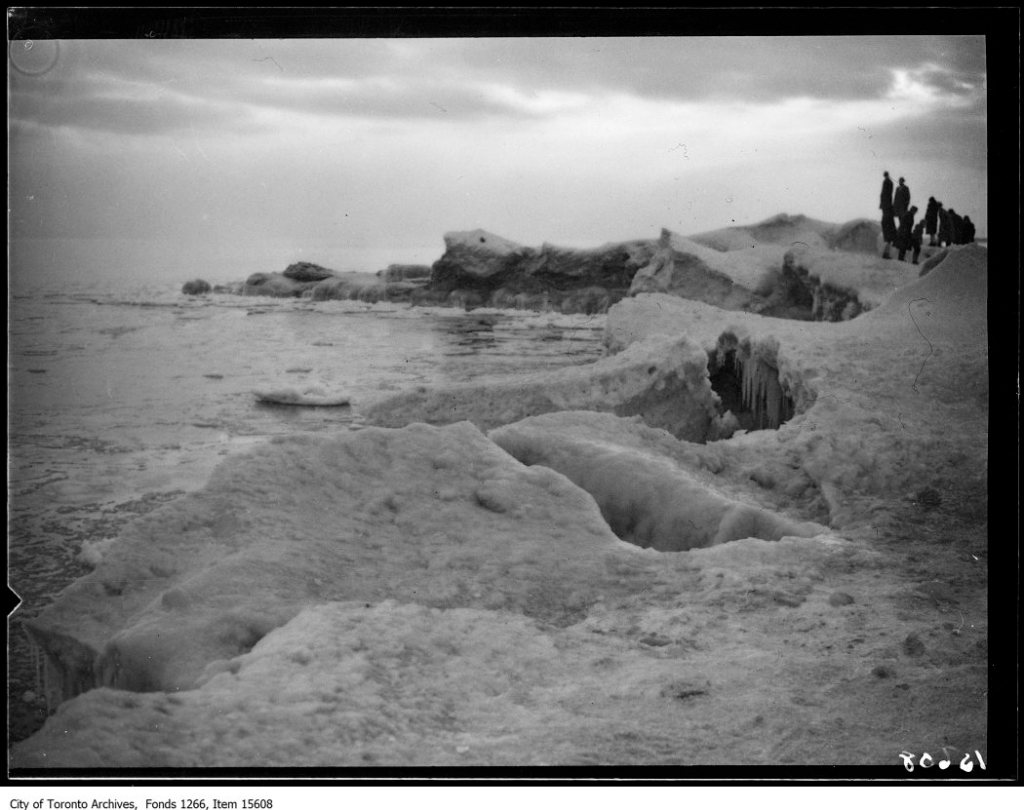

When I look at these photos of ice formations from long ago and when I walk along a beach today, I think of our coast’s glacial geology.

Like the photographer and his dog, I enjoyed the wild and strange icescape.

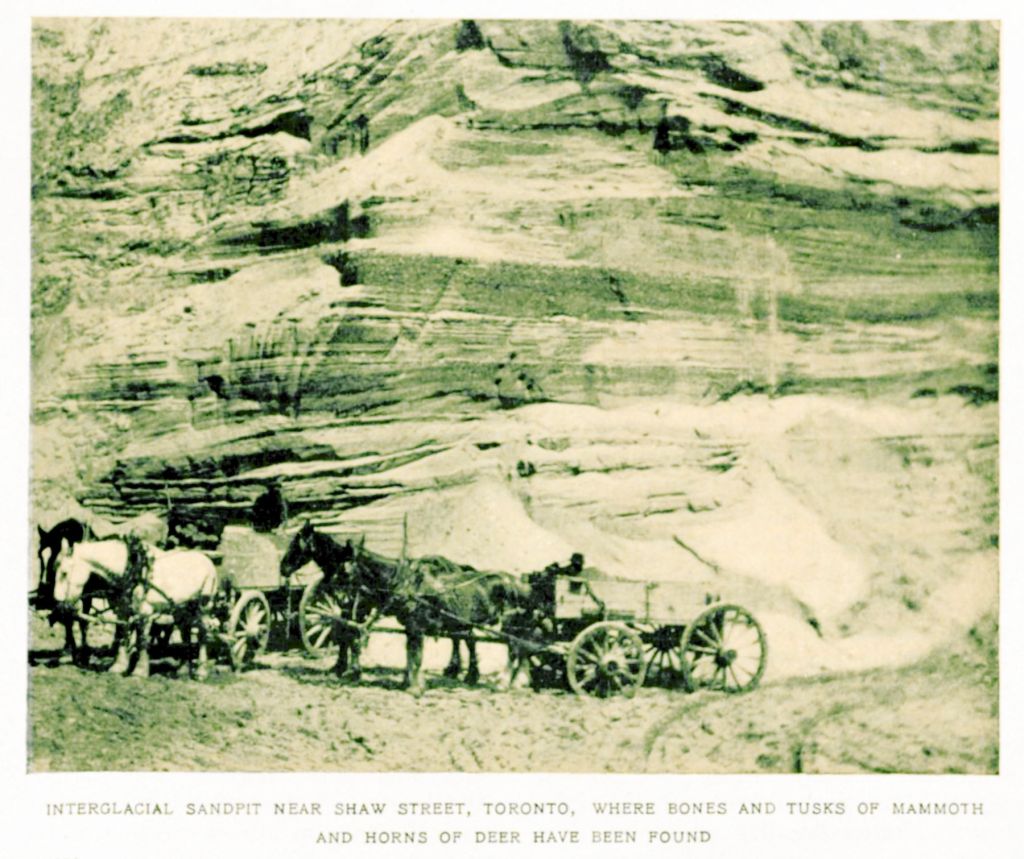

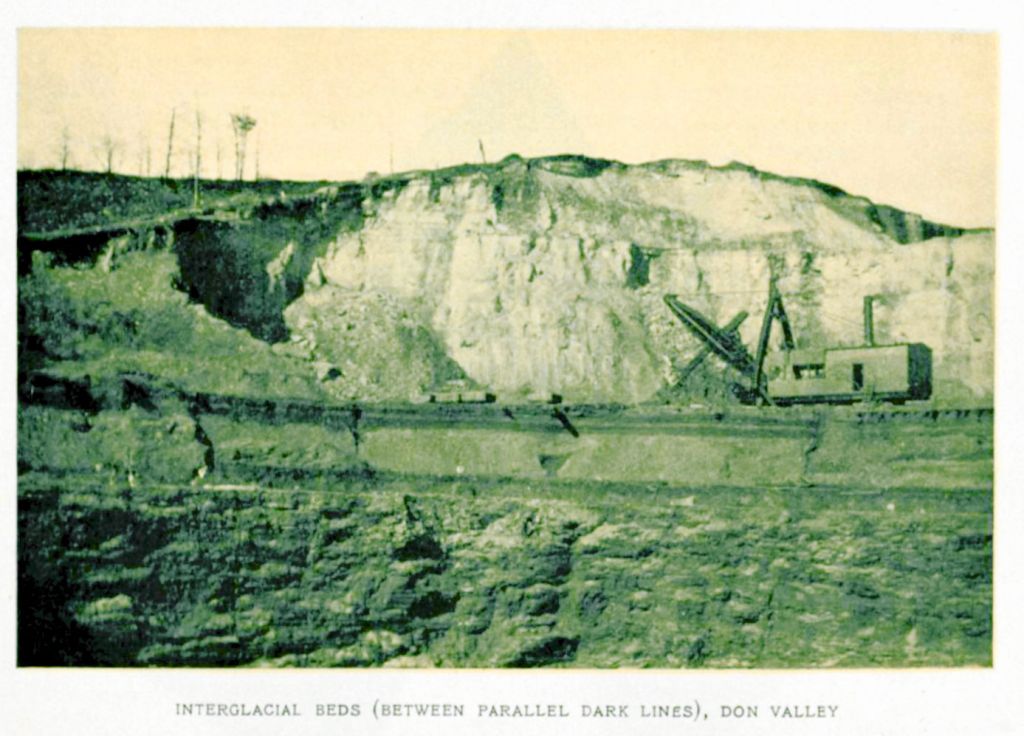

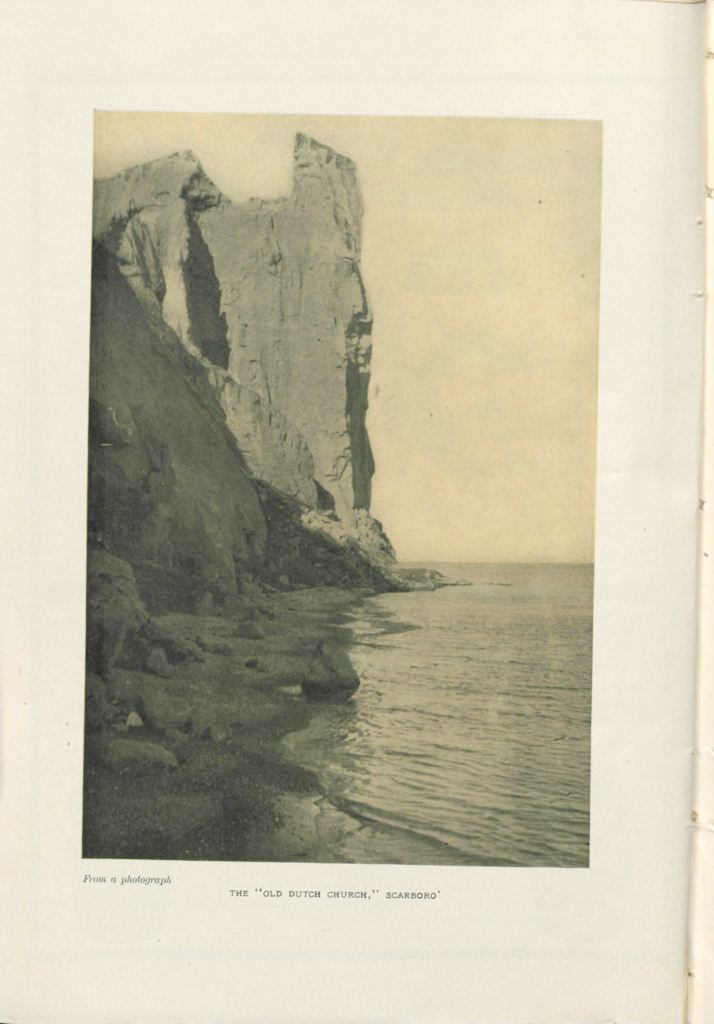

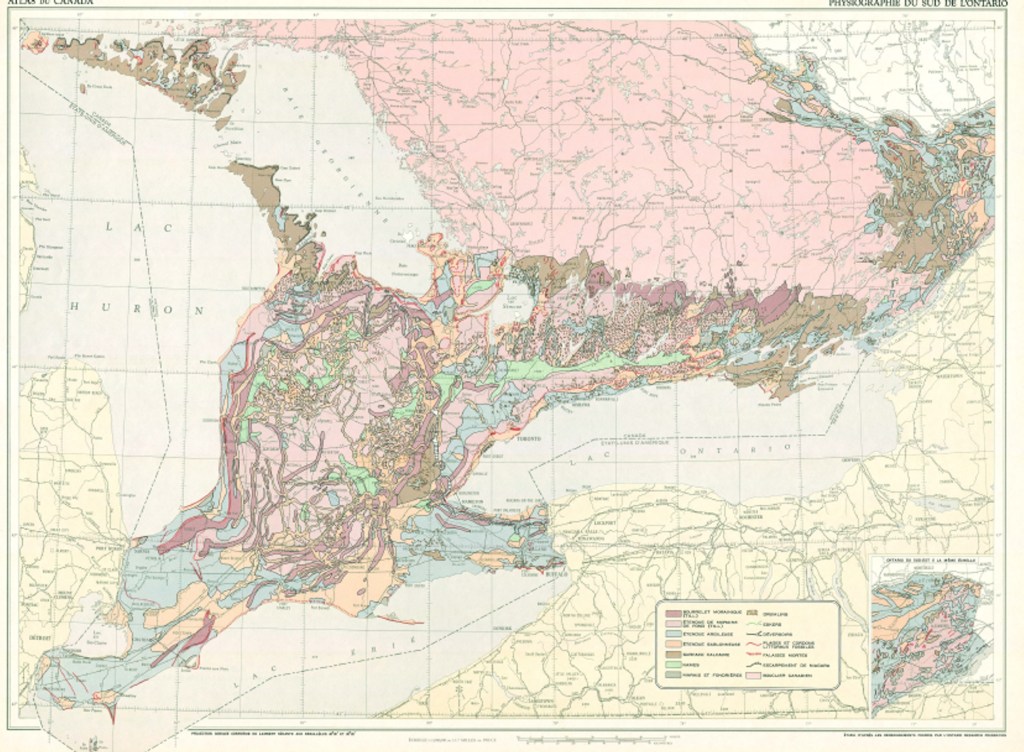

Since I was very young, I was familiar with ice caves, crevasses and the world of the last Ice Age, thanks to my Dad. And when I walked with my father along the shore of Lake Ontario and saw these giant chucks of ice, we talked. Later on I learned about geomorphology and the work of Dr. A. P. Coleman[1] who pioneered research into Ontario’s glacial past and L. J. Chapman and D. F. Putnam’s, The Physiography of Southern Ontario, 1957. And more recently the work of Nick Eyles and Laura Clinton and their Toronto Rocks: The Geological Legacy of the Toronto Region has inspired me along with the many walks and talks by the geologist members of the Toronto Field Naturalists.

You can download L. J. Chapman and D. F. Putnam’s map as a PDF at:

https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/d22354e8-cb01-5262-aed5-1de48d1ffb0a

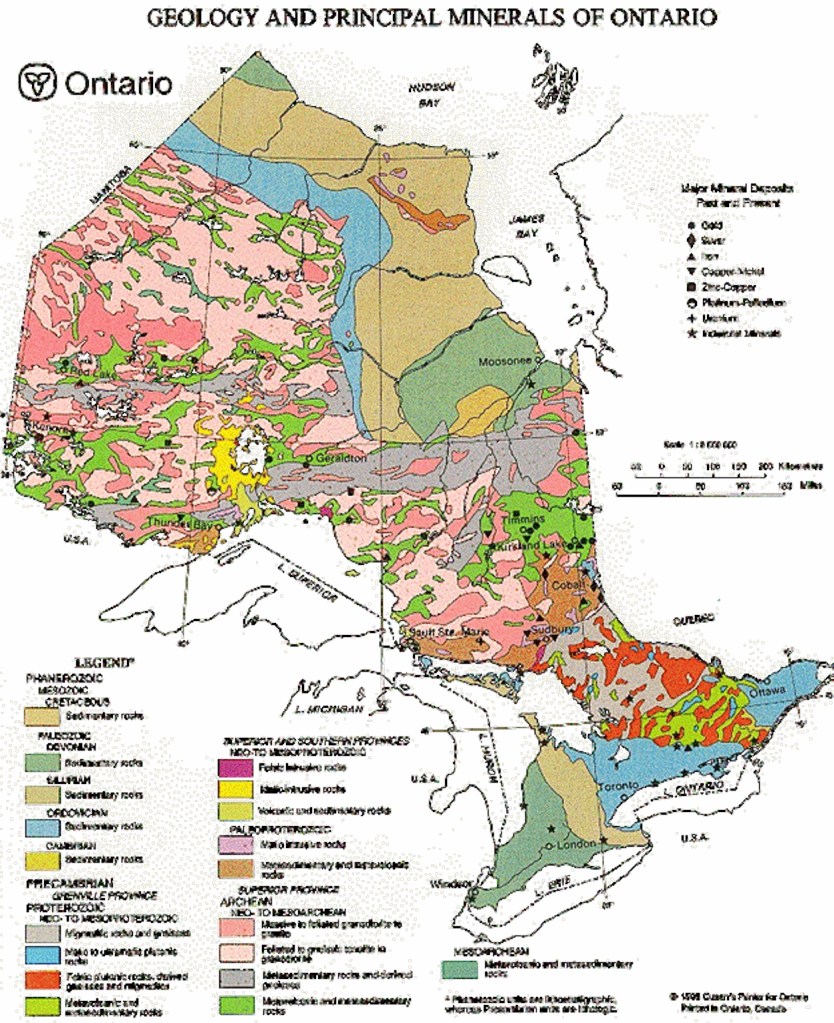

I’ve always been fascinated with rocks. The oldest rocks in Ontario are found on the Canadian Shield, itself formed as an ancient mountain range. Volcanic activity buried the worn down remnants and heated that ancient rock creating new rocks. The changed material, metamorphic rock, still makes up much of the Shield. Then ions later a tropical sea covered Southern Ontario, leaving sand and clay deposits than hardened over time into sandstone and shale. I have in my collection limestone with ripple marks and a lovely shale piece with a fossilized trilobite.

If we could read Toronto’s geological history like a book, we would find a huge gap between the ancient rocks of the Shield to the rocks underlying Toronto. It is as if someone tore not just a few pages out but whole chapters which is, incidentally, why we don’t have dinosaur fossils here. The Jurassic chapter is missing. Part of the reason for that is ice. Long ice ages with their glaciers ripped apart the surface tearing out those chapters. It was as if the Antarctic ice cap dropped on top of Ontario.

The Wisconsian glaciation episode, from 75,000 to 11,000 years ago, saw our most recent ice sheet. The massive Laurentide ice sheet crept inexorably forward. The ice, under the pressure of its own weight, changed. The structure of ice became like a stack of playing cards with the crystals sliding over each other like playing cards. The last glacial maximum, when the ice reached its greatest extent, was about 25,000 to 21,000 years ago.

Ontario’s ice sheet was over three km (two miles) thick at the centre and at least a half at kilometre thick at the leading edge or snout. The moving ice scraped off the soft sedimentary rock, transporting the debris hundreds of miles before dropping it. The ice scalped off the edges of the Michigan Basin, pushing the rim further and further west. The hard dolostone of the Niagara Cuesta resisted, but the ice scoured and polished it. Huge waterfalls poured over the edge of the Escarpment. Water filled the basins of old river systems deepened by the ice. The Great Lakes formed.

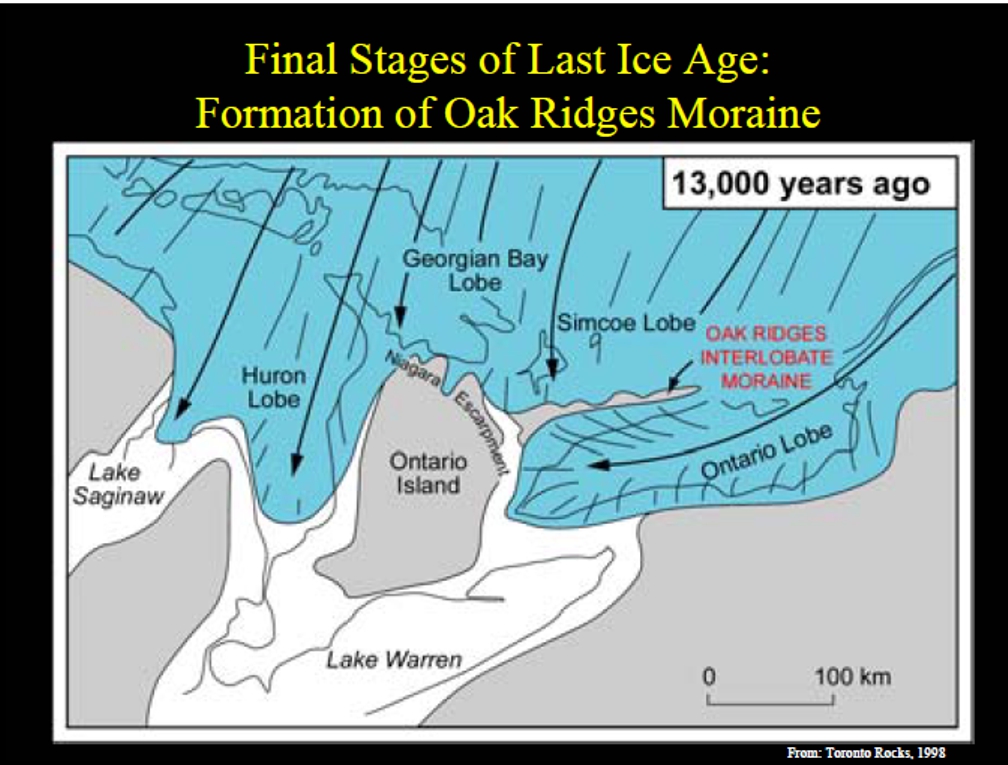

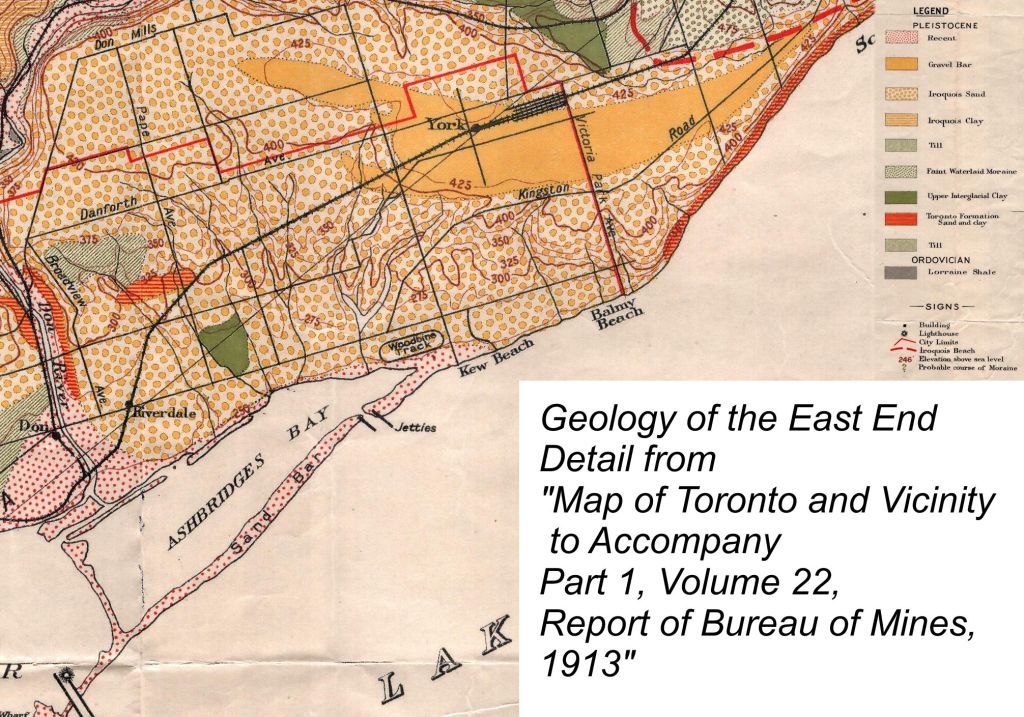

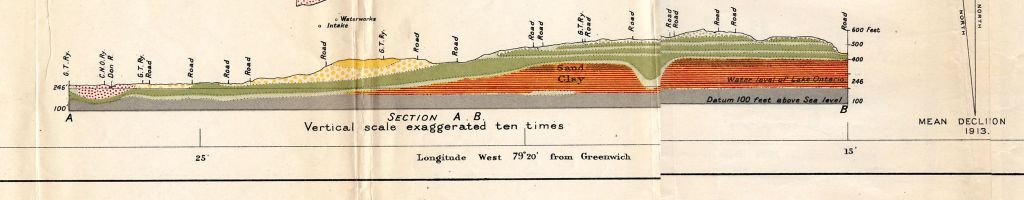

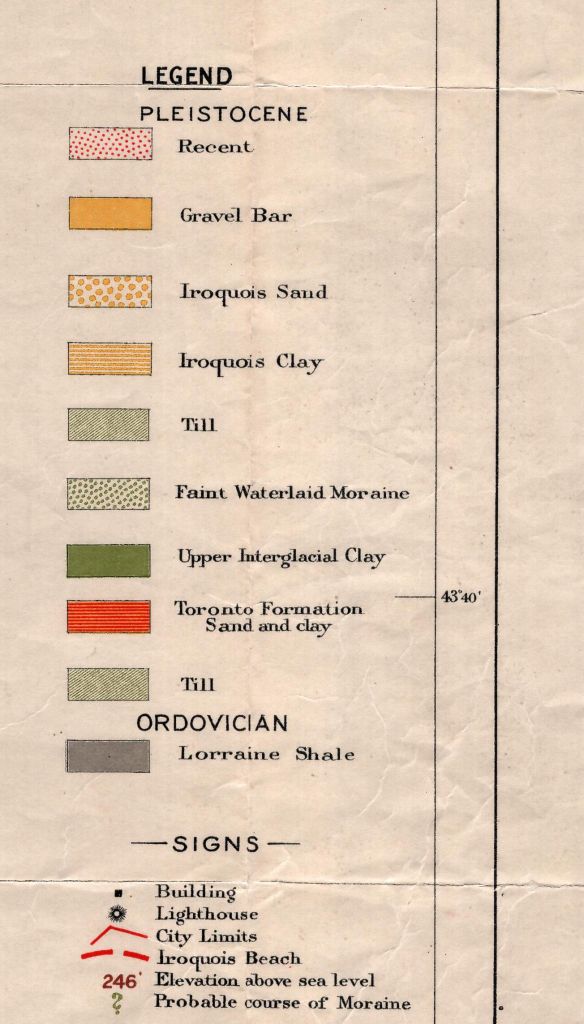

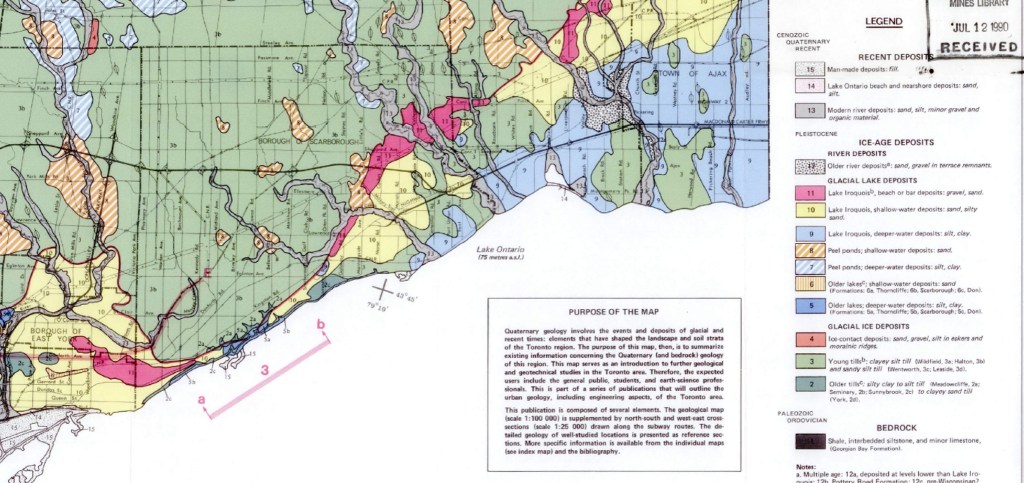

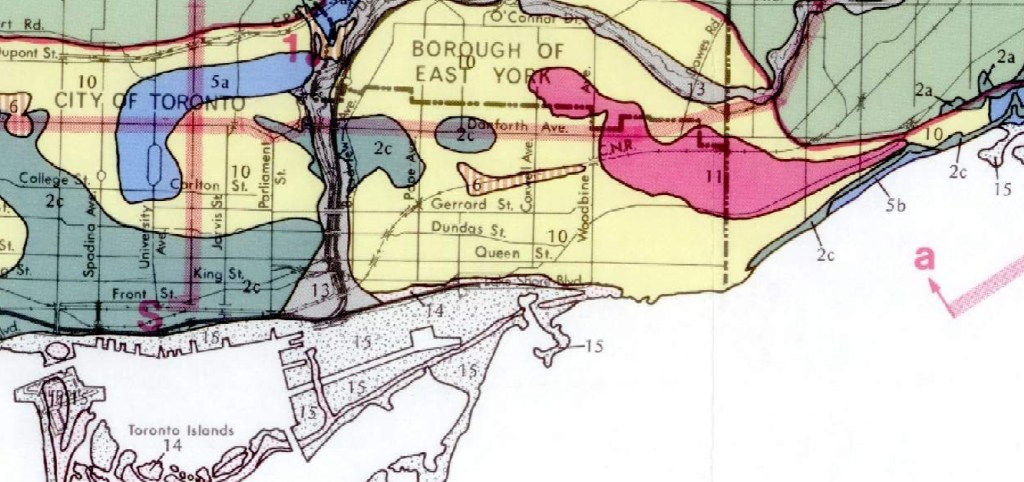

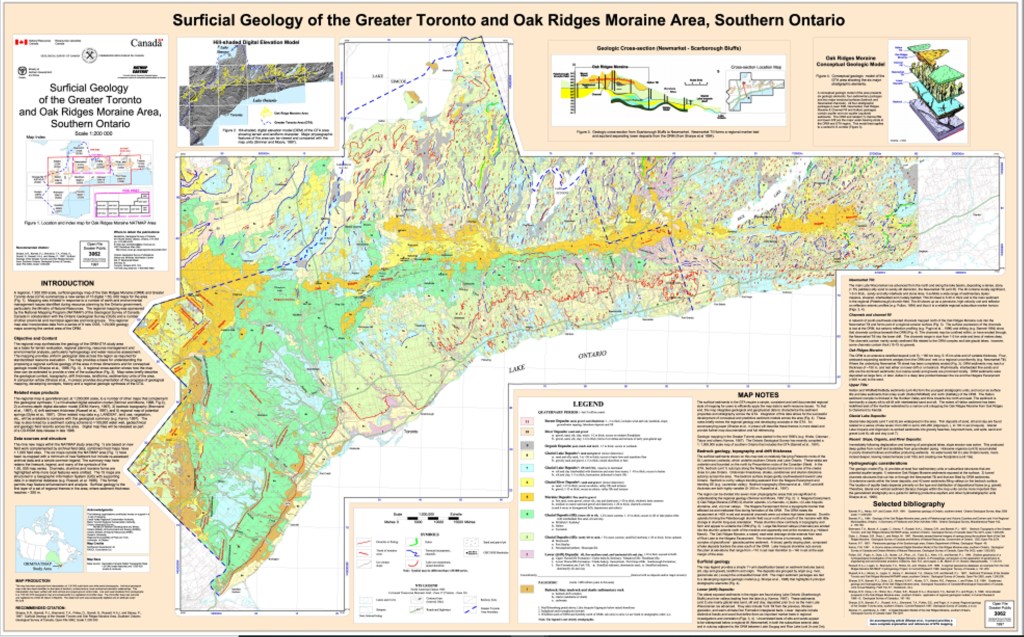

The water, ice and rock of the last Ice Age radically changed the geography of Ontario. It left many glacial features behind: the Peterborough drumlin field, the Oak Ridges moraine, the Guelph kame field, the Lake Iroquois shoreline, wave-cut terraces, erratics, river rocks, deposits of till, sand bars, outwash gravels, clay, etc. Varved deposits and buried river channels are other clues to the ice sheets’ presence. Glacial debris buried bare bedrock and earlier deposits. It is not hard to find polished rock and bedrock striations in “cottage country”.

The “glacial drift” is about 26 metres thick over most of Toronto. Erratics can be found and traced back to their sources. Smaller rocks, i.e. field stone, are another reminder of glaciers. They are made of granite, schist and gneiss unlike the bedrock limestone and shale. [2]

Glacial deposits here include:

a) glacial till – an unsorted mixture of sand, silt and clay;

b) glaciofluvial deposits – materials washed out by rivers of glacial meltwater;

and

c) glaciolacustrine deposits – material laid down by glacial lakes.

The weight of the ice depressed the crust of the earth. It has been rising back up ever since, but rebounded more rapidly in the north-east where the ice was thicker. Now “isostatic rebound” is lifting the east end of Lake Ontario faster than west. This isostatic rebound caused higher lake levels and reduced the gradients on streams like Duffin’s Creek, the Humber River, the Rouge, formed drowned river mouths.[3] The Lake Iroquois shorecliffs form a line of hills across Toronto. Between the shorecliff and Lake Ontario is a plain made up of clay and sand deposited on Lake Iroquois’ bottom. It is the “Iroquois Plain”.

When the Earth’s climate warmed, the ice began to melt and the glaciers retreated. But I am reminded of them wherever I look along our coast and especially when I see ice on the shore.

Definitions

Crevasse:A crack or series of cracks

Drumlin: The glaciers formed drumlin fields. The one at Peterborough is famous. Drumlins are hills shaped like a teardrop or whaleback. These drumlins formed in the lee of a bedrock obstruction under the glaciers.

Erratic: aboulder that was carried here by the glaciers. Some are small, but some are as big as a house. They wereonce believed to be carried here by the flood in the Old TestamentBible which is why we get the term “glacial drift”. Somehow the rocks, people believed, drifted here.

Esker: Streams and rivers flowing through the glaciers themselves left eskers: winding ridges of gravel.

Glacial drift: debris, rocks, gravel, sand, left by the glacier.

Grooved surface: carved rocks, rasped by debris in bottom of the glaciers. Other rocks were polished by the debris.

Hummock: [lake ice] a smooth hill of ice that forms on the lake ice surface or shore from eroding ridges

Ice cave: A cave formed in or under ice, typically by running water or wave action.

Kame: Kames are conical hills formed by debris deposited by the enormous waterfalls.

Kettle lake: The glaciers left kettle lakes, deep, cold lakes formed from blocks of ice buried in the glacial till.

Moraine: Along the edges, at the ends of and between the ice sheets, the melting ice dumped ridges of unsorted material. Geologists call these ridges moraine.

Outwash plain: Outwash plains are areas where melting water swept sand and gravel over flat land.

For a sense of what a glacier was like with its crevasses, hummocks and ice caves see:

Into the Heart of Sólheimajökull – Exploring the Stunning Crevasse Fields and Ice Caves

[1] Map/ Diagram. A.P. Coleman and H.L Kerr, 1913, “Map of Toronto and Vicinity to Accompany Pt. I, Report of the Ontario Bureau of Mines, [detail 1]” in Annual Report of the Bureau of Mines. Toronto: Bureau of Mines. Royal Ontario Museum, Department of Natural History Collections.

[2] For a thorough discussion of Ontario’s glacial history and our surface topography, see Chapman, J. and Putnam, D. F. The Physiography of Southern Ontario. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966.

[3] Westgate, John, Ph.D. (Professor of Geology, University of Toronto at Scarborough) “Geology of the Oak Ridges Moraine”. An Illustrated Talk, Toronto Field Naturalists, April 2, 2000.

Leave a comment