In January 1912 a fierce winter storm cut the little fishing settlement on Fisherman’s Island off from the rest of the City of Toronto. These images tell the tale of that storm, but there’s more to this story than that. If you scroll down, I’ve included a rough time line of Fisherman’s Island’s history, many transcribed articles, and lots of photos and maps. Enjoy! And stay warm and safe on this cold winter’s day of January 21, 2025.

Time Line Fisherman’s Island

Sand Bar and Fisherman’s Island: The areas constituted natural features of the sandbar and Peninsula. Pre contact aboriginal healing. Wild rice. Fishing. Investigation of the Sports Fields on the south side of Unwin Avenue. Dug a five metre wide, 1.5 trench. Archaeologists. Stratigraphic profile: deep layer of fill (construction rubble, municipal waste in the form of trash and cinders) over a discontinuous horizon of homogeneous sterile sand generally 30-40 cm thick on top of lake bottom silts and clays. Sand is the bottom of the sandbar and would have been below the surface of the lake.

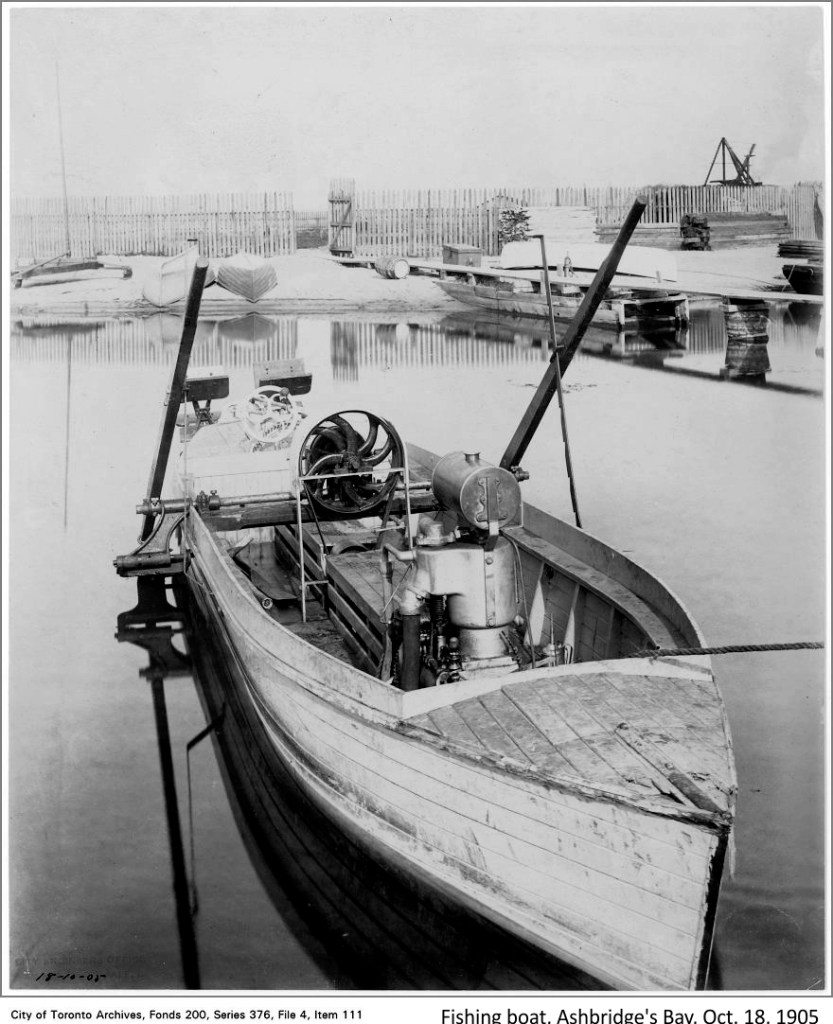

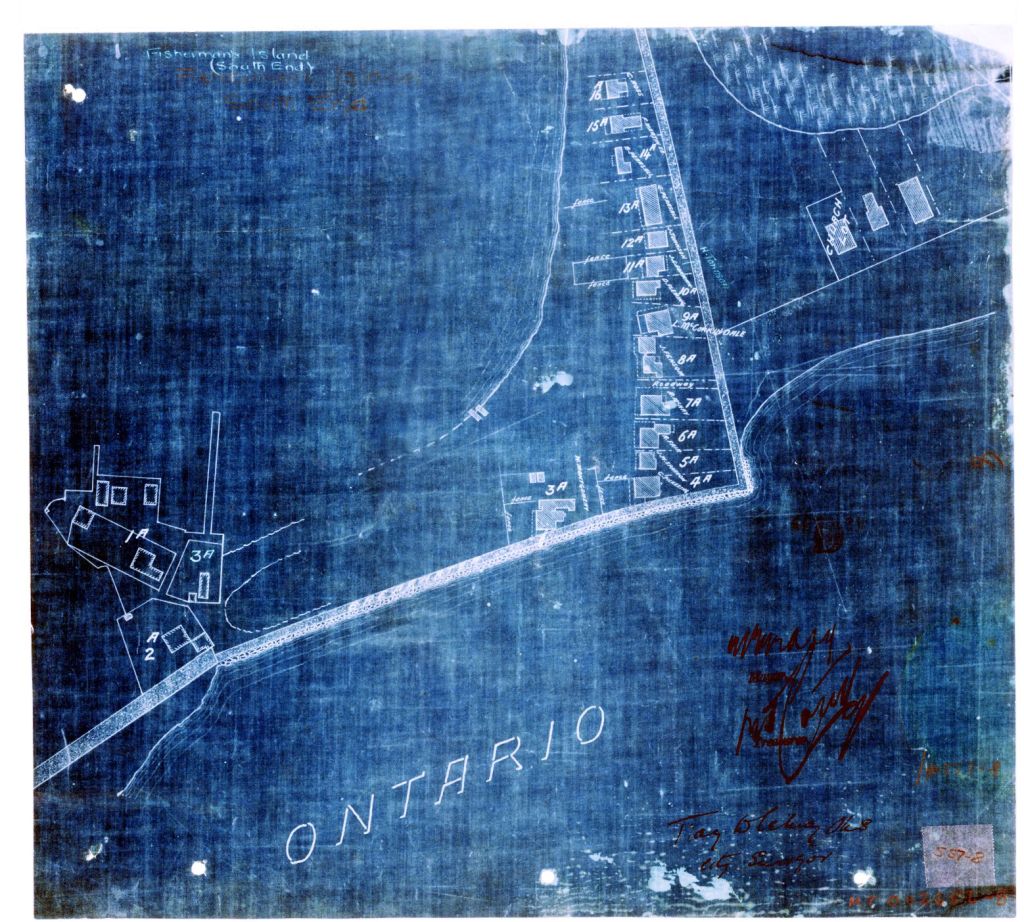

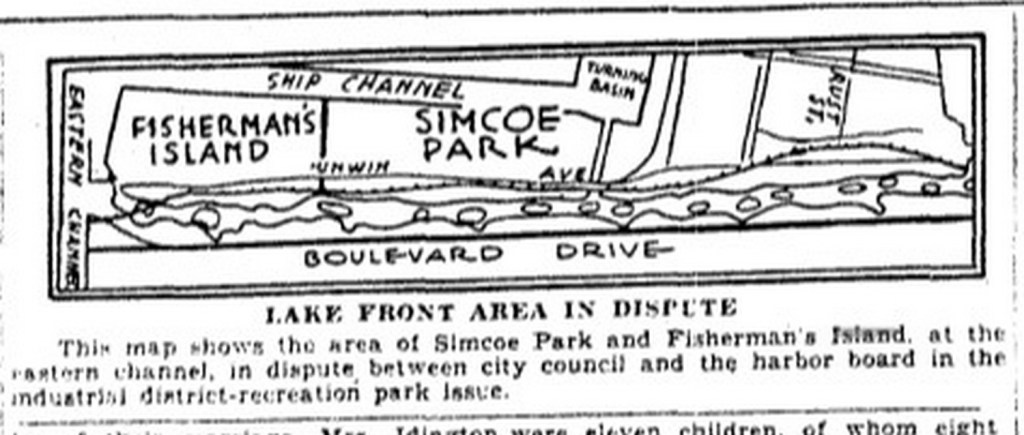

Simcoe Beach Park, Fisherman’s Island Cottages, Boat Houses, etc. Small-scale fishing enterprises lined some sections of the harbour edge while on the sand bar and outer headland, there were several clusters of cottages. Mostly frame buildings built on footings or shallow timber sleepers. Boardwalk.

Most of this area consists of modern fill that was dredged, dumped and engineered in the early 20th century. Some parts of the port lands were completed as late as the 1960s.

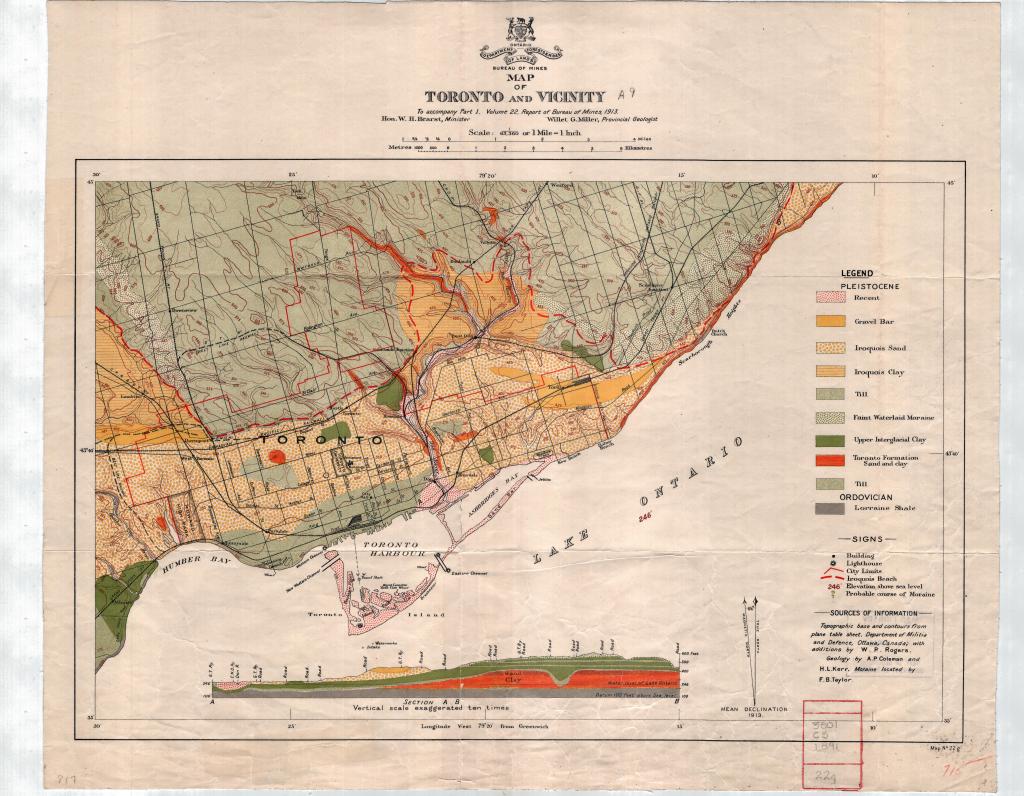

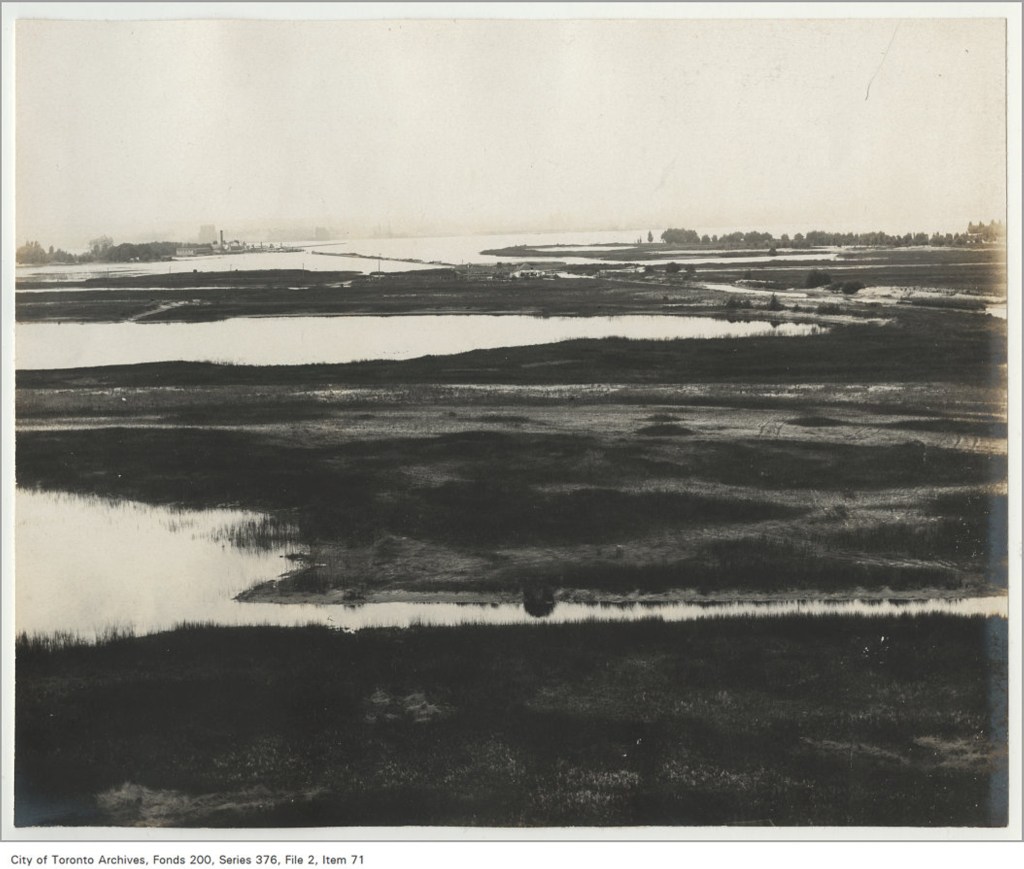

Since the end of the Pleistocene, isostatic uplift has continued to gradually elevate Lake Ontario. Raised lake level and flooded river mouths. Extensive coastal marsh – Ashbridge’s Bay.

Sand spit formed by eroded sediments from Scarborough Bluffs. Longshore current. Deposition. Before 7000 BP to 12000 BP the level of lake much lower and shoreline further south.

10000 BP projectile point found at TGH site at King and John Streets.

The Peninsula began forming c. 7000 BP. Shallow sandy. Not much soil. Regosol weakly developed mineral soil. Organic matter in depressions. Folling topography, dunes and swales, ridges, lagoons.

5000 BP Lake Ontario shoreline established more or less as it was in the 1790s. No evidence of native occupation therefore before that. The Don River had as many as five mouths in the area and the isthmus was cut by two of them.

1600s century first contact between Europeans and Wendats. French explorers, traders, missionaries.

1649 Wendats defeated by Fire Nations. Seneca took control of Toronto area. Carrying Place Trail.

1700 Mississauga defeated Haudenosaunee and began moving south into the Toronto area.

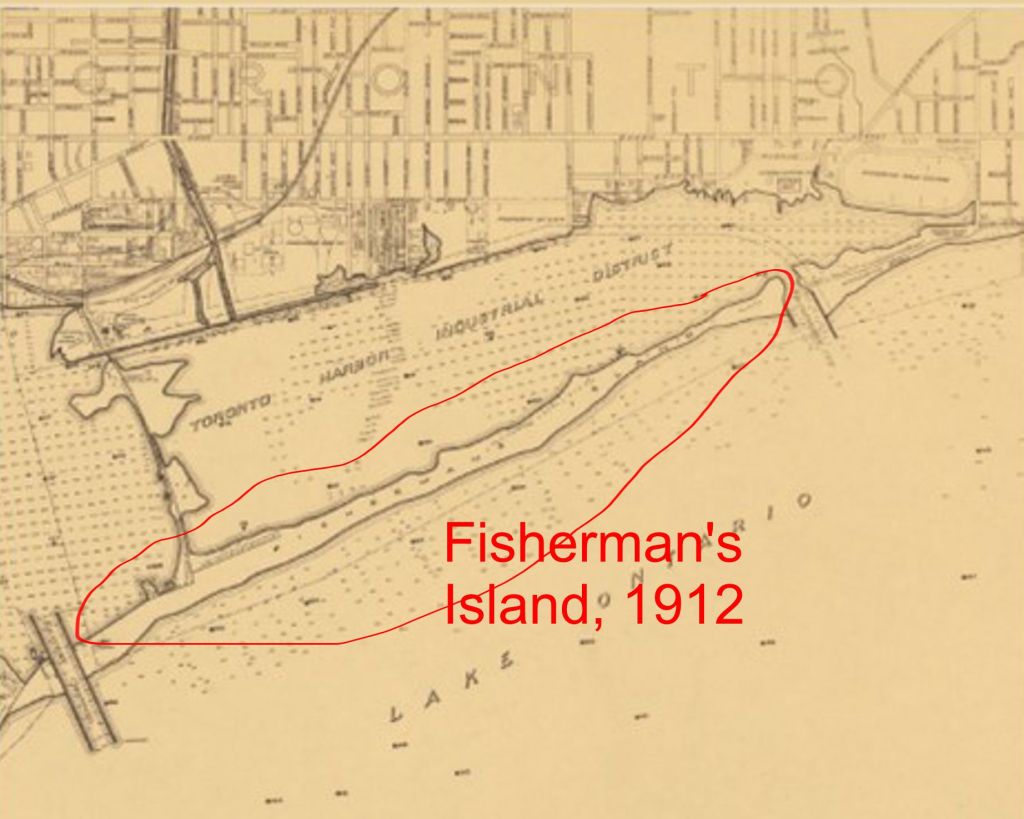

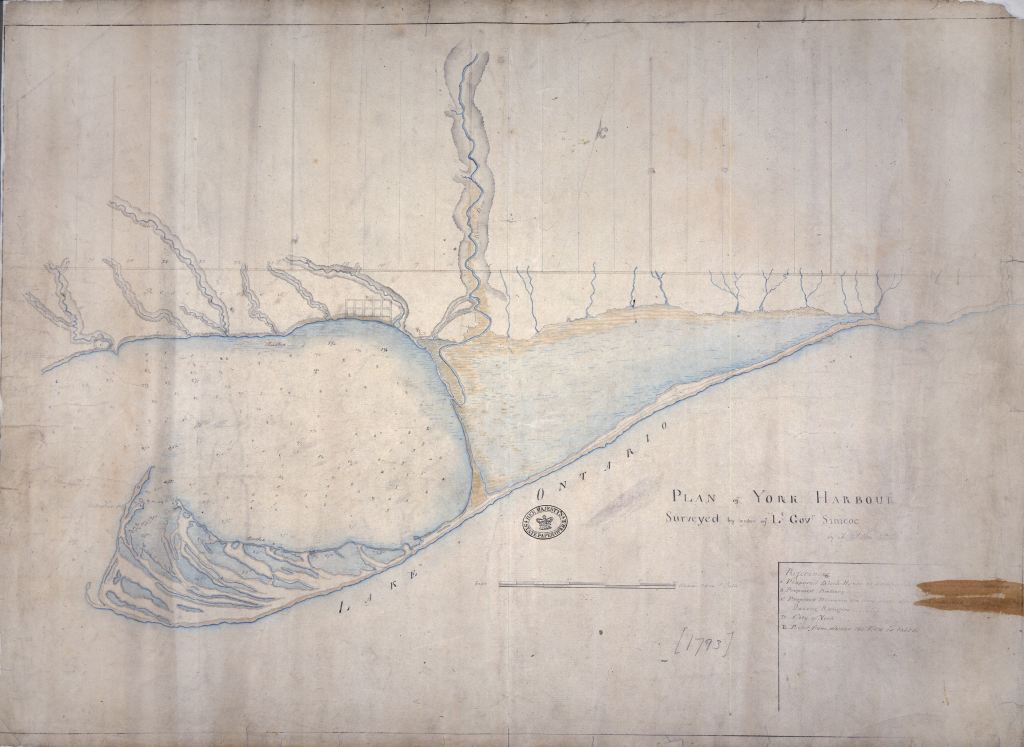

1793 Simcoes arrived at Toronto and renamed it York. 1793 A. Aitken’s Plan of York Harbour. Shows “The Bend” and sandbar at the east end of the harbour separating Toronto Bay from Ashbridges Bay. Don had two mouths.

1830s development of Toronto necessitated building of harbour infrastructure. Wharves and piers. Freestanding crib structures of timber. From at least 1830s a carriage path crossed the Ashbridge’s Bay bar.

1837 Windmill line established.

1842 Seven new wharves had been added. More and more wharves further and further into the lake.

1820 By 1820 first major wharves in places (King’s, cooper’s and Merchant’s wharves).

1842 Seven new wharves had been added. More and more wharves further and further into the lake. Filled the slips between them – landfill process known as “wharfing out”. Created relatively small blocks of new land mostly between church and Berkeley in the 1870s and 1880s.1850s

Three Major railways: Ontario, Simcoe and Huron Railway (later called the Northern Railway(, the Great Western Railway and GTR entered Toronto in 1850s. GTR. Gzowski. Cut down the south face of original shore cliffs and filled almost the whole waterfront. Causeways for track beds and areas for rail yards and stations.

1858 On going erosion. A process of building up and tearing down. Net gain in sediment until 1850s then a period of erosion and decline in sediments from the Bluffs. Periodic catastrophic erosion. 1852 storm breached the Peninsula, widened to 45 metres. Closed. 1858 storm breach to 450 metres. Grown to 1200 metres by mid-1860s.

1860s lakefront changed dramatically. Filling in of harbour front Bathurst to Parliament with the development of the Esplanade as a rail corridor.

1870 Filled the slips between them – landfill process known as “wharfing out”. Created relatively small blocks of new land mostly between church and Berkeley in the 1870s and 1880s. Pressure on waterfront in late 19th century. Bigger “crib and fill” landfilling. Sewage, municipal garbage (mostly ashes), construction debris, dredge from harbor bottom. Railway companies. 1870 a long timber crib breakwater was built on the south side of the Don River – roughly at the foot of Cherry Street into the harbor to a point below Berkeley Street., 1886 the rotted remains of the breakwater abandoned.

1881 Famous American civil engineer, James Eads, report on the preservation of the Toronto Harbour recommended a breakwater with a double row of sheet piling between the harbour and the “Bend”.

1882 April James B. Eads report submitted to Dominion Parliament. To prevent encroachment of Ashbridge’s Bay on Toronto Bay. Feared destruction of harbour. Sheet piling around Eastern Gap. Breakwater. Eastern Gap permanent 300 feet wide and 18 feet deep. The Government breakwater was three feet high. Western Gap not closed as Eads wanted it to be. Breakwater originally 4,300 feet north south. Groynes built on Fisherman’s Island to George Gooderham’s house on the south side of the Island. Piles of cedar, cross braces of white pine and waling of rock or grey elm. Work began February, 1883. Brush used as fill. Pile driving. Sheeting. Globe, Feb 9, 1883

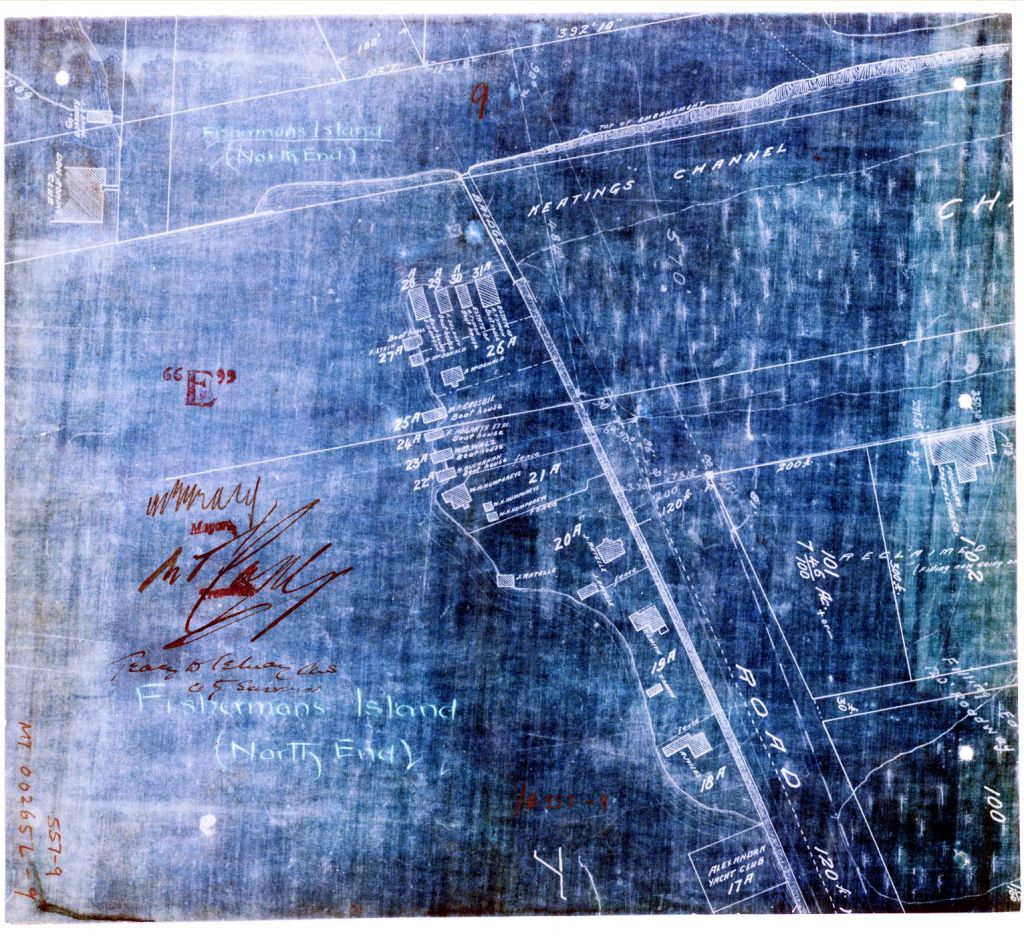

Eads plan – Government breakwater. Eastern Gap made permanently navigable – dredging. Government breakwater. Built by the Dominion government in 1882 to prevent the movement of Ashbridges Bay into the harbour. The structure consisted of a double row of sheet piling, which served as retaining walls for rock fill. Heavy storms in the sprint of 1882 caused such severe damage that the length of the piling had to be considerably increased. The work was completed in 1882 -1883. The feature followed a curving line from the Don breakwater to Fisherman’s Island, bending wet to the edge of the Eastern Gap. The breakwater did not follow the natural line of the spit, though the top formed a dirt pathway that later supported the horse-drawn wagons, automobiles and the hydro lines of the local cottagers. The breakwater regularized a path system that had existed since earliest times. Under pressure to improve the sanitary conditions in Ashbridges Bay, the breakwater was breached in, 1893 by Keating Channel (E.H. Keating, City Engineer).

1883 From early on the squatters on Fisherman’s Island had a life saving role. In, 1883 eight workingmen were stranded on Fisherman’s Island when a gale blew up. There were only two houses on the Island (Smith was one). The men sheltered there. . Globe, Nov 17, 1883

1884 The Smith Family (Thomas and Annie Smith) settled on Fisherman’s Island. First to settle there. Abundance of game and fish. Smith’s had eight children. Fishermen – prize catch whitefish. Children caught frogs which they sold across the Bay. To reach the mainland they used a row boat. A large, flat scow with railings and attached at either end by rope was hauled across by hand.

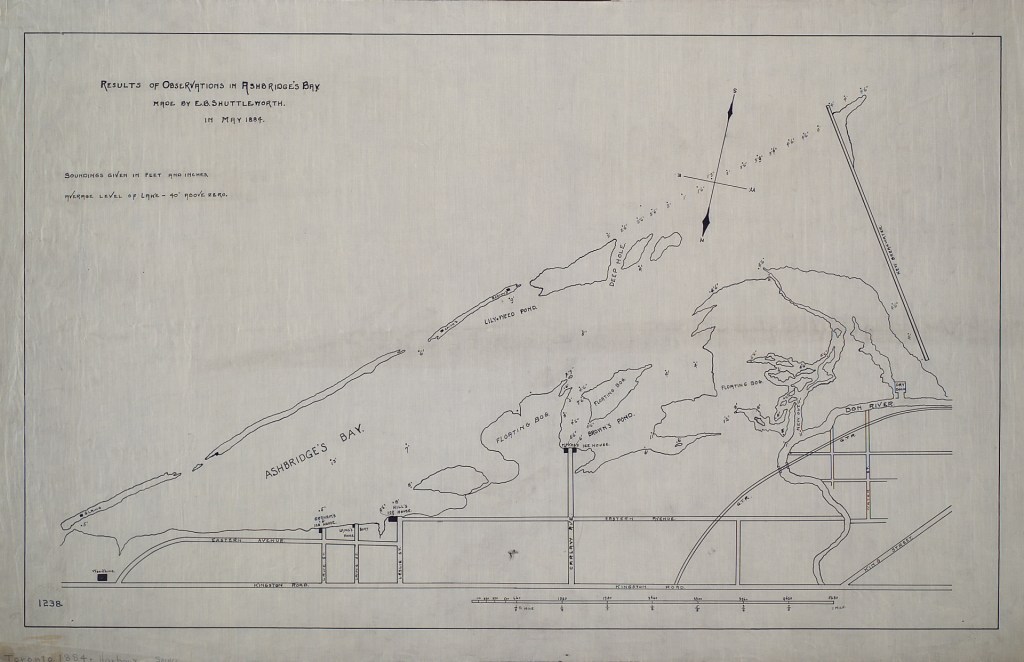

1884 E.B. Shuttleworth Map, May 1884, shows three residents on the “Sandbar” Langs at the bar east end, Woodbine Beach. Smiths and Beatty’s on Lily Weed Pond. Woodbine Beach was the extreme eastern part of the sandbar. Separate from Fisherman’s Island in the 1860s when the Lake breached the sandbar.

1884 The federal government constructed a breakwater along the western side of the sandspit creating a new shape to Toronto’s inner harbor and consolidating a north south passage to the Fisherman’s Island. Small-scale fishing enterprises lined some sections of the harbour edge. On the sandbar and outer headland there were two clusters of cottages. Most cottages were built by squatters but about 20 cottages on the outer bar were located on surveyed lots that were leased. Lakefront of Fisherman’s Island had a wide boardwalk.

1886 to 1909 a number of development proposals.

1888 June 7 Frank Abel Smith born. “Bird Smith”. Used Japanese mist net. Bird bander. Made model birds. Taught carving to Junior Field Naturalists at ROM.

1889 May a contract was issued to improve the Eastern Gap. A channel was dredged 300 feet wide to 12 feet deep. The shoreline on either side was armoured. 1889 Sessional Papers, Parliament of Canada, Volume 23, Issue 13, p. xxviii

1893 Coatsworth’s Cut made the separation of Woodbine Beach and Fisherman’s Island. permanent. Both were cottage communities in the summer. New Windmill Line. Expansion to allow deep water piers without need for further dredging. New lake boats had drafts greater than 10 feet. City built a new shore wall of rock-filled timber cribs on the New Windmill Line and filled with municipal garbage. Work completed by, 1899. Keating Channel dredged by City Engineer Dept.

June 23 On a division it was decided, on motion of Ald. G. Verral, to delay action for two weeks until the estimates are passed. A sub-committee was appointed to consider what rent squatters on Ashbridge’s bay shall be required to pay. Globe, Friday, June 23, 1893

Many people summered on the island. Favored by sportsmen for hunting (e.g. plovers, ducks. At about 2/3 of the distance from Coatsworth’s Cut to the Eastern Gap the sandbar was 200 yards wide. There was a dozen cottages or shanties there. Crossed by boat. James Forman of the City Assessment Dept. had a cottage there. James Grandfield accidentally killed himself with his own gun. Hunting accident. 32 years old. Shot by his own Gun Globe, Sept 20, 1893

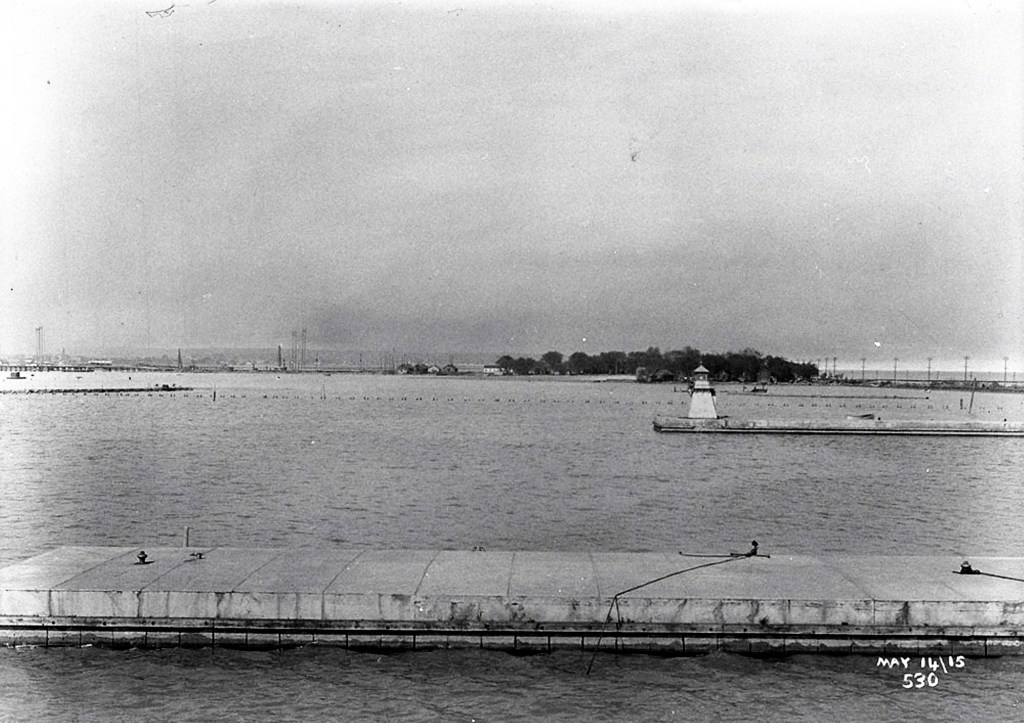

1895 Complaints that Eastern Gap had no lighthouse. Vessels having trouble. Lighthouse being constructed, 1895 at the south end of the 2,420 foot long pier. “The breakwater pier connecting the east pier with Fisherman’s Island is also completed, and as was expected, a considerable sand-beach has formed in front of it.” Break water pier Globe, Jan 6, 1895

1896 Improvements to the Eastern Gap. At first Eastern Gap in 1858 was only 150 feet wide but in, 1889 the Gap was widened to 2,170 feet. The depth was 2 feet 9 inches to 4 feet 6 inches. The east pier was now 2450 feet long and the wet pier 1700 feet long. The channel between 400 feet wide and 16 feet deep. The breakwater connected the east pier to Fisherman’s Island. “This condition of things is in striking contrast to that which prevailed before the present breakwater was constructed, when the waves lashed the wharves along the city front furiously, and were big enough to lift the schooner Persia, then owned by Mr. Morgan Baldwin, the present Harbormaster, partly on to the top of the wharf.” George Gooderham’s house was on Toronto Island. Knew that the new pier would at the Eastern Gap would cause a beach to form there. “indeed, the deposit of sand at that point is already several feet deep, and is forming a beautiful beach, which before long will be far ahead of Burlington Beach at Hamilton and will prove an attractive summer resort for our citizens.” City Engineer recommended groynes along the island to break waves and encourage deposition of sand. 80% of ship traffic in and out of the Harbour was now by the Eastern Gap. Toronto Harbor Globe, April 29, 1896

1897 FOUR LIVES LOST. A Score of Children Struggling in the Water. The dead were Robert Long (7), Gertie Harvey (12), Albert Driscoll (9) and Willie Bythell (9). Public bathing was under the direction of City Commissioner Coatsworth but the Board of Control had recently taken charge of it. Mayor Fleming had set aside swimming areas at the western end of Toronto Island and at Fisherman’s Island. They provided a raft to carry the boys over from the city after the new Cherry street swing bridge opened. The breakwater was interrupted by a channel known as McNamee’s cut. The piling dividing Ashbridge’s Bay from Toronto Harbour had a path on the top of it. The water dropped off on either side of the path to four feet deep and so could be dangerous to children too. Ald. Lamb had asked the City Works Dept. to construct the raft which was used to ferry people and goods across to Fisherman’s Island. He didn’t consult anyone else except works Commissioner John Jones. It was cheap and would help people, especially young boys, get to the swimming beach on Fisherman’s Island. It was cheap to build out of old lumber and was six feet wide and sixteen feet long with railings at four foot in height and was pulled across by chains. No one was left in charge of it, though the watchman at the nearby city dump was supposed to keep an eye on it. 18-20 children were on the raft made of planks over a couple of logs. A chain attached to the banks on the north and south allowed people on the raft to pull themselves across hand over hand. According to a report in the Globe, “the children were playing on the raft and rocking it to and fro. Suddenly it tipped to one side, then to the other, and went over.” Yachtsmen helped rescue the children as did people rom Fisherman’s Island and older boys on the raft. Hector McDonald from Fisherman’s Island dragged for the bodies. He was in charge of the swimming station on Fisherman’s Island. Globe, August 23, 1897

THE DROWNING ACCIDENT Ald. Daniel Lamb ordered the building of the raft. The raft was meant to carry only 3-4 people. The land fronting where the raft was left was fronted by the Dry Dock Company. [The raft was subsequently replaced by a punt and then a bridge.] The path was across the dry dock property and was therefore not on public property but widely used by the public. Previous to the raft the public had used a punt. The people of Fisherman’s Island had not asked for the raft to be built. Globe, Aug 30, 1897

Five bodies were found. Thomas Smith won a Royal Canadian Human Society life-saving certificate. A bridge was built to the mainland. Safe access. Thomas Smith saved 30 people from drowning during his live. He was a commercial fisherman but also had a boat livery.

1898 Thomas Hector MacDonald (43) and his niece Mamie McDonald (13) drowned in McNamee’s cut. Thomas McDonald “lived in one of the cottages on Fisherman’s Island, or the sandbar, as it is sometimes called, and his young daughter, Mamie. Francis McDonald, Thomas’ brother, Francis, was able to save Thomas’ wife, Liz. Five children drowned at McNamee’s cut the August before. It was first thought four children drowned but five bodies were recovered. The cut was about 25 yards across and the McDonalds used a scow to cross it. The Scow sank. “Thomas hector McDonald was the man who saved the lives of many children in this [Aug.] disaster. He was a strong sturdily built man, and his life about the Island had made him perfectly fearless in the water. He was an accomplished swimmer, and has won a medal for his proficiency in this sport.” Fatal M’Namee’s Globe, March 7, 1898 [Francis Bernard McNamee was a contractor and canal/road builder responsible for dredging Toronto Harbour.]

“To Reach the Sandbar. The lamentable accident at McNamee’s cut on Saturday night has again directed attention to the necessity for some means of crossing the channel at this point being provided. Ald. Lamb is stirring himself in the matter and is pushing a project for constructing a plank walk on top of the breakwater, 8 feet wide, equally divided between foot passengers and bicyclists, to the Fisherman’s Island. The scheme involves piling and a 30-foot drawbridge across the centre of the channel, high enough to allow ordinary sailboats to pass underneath. Mr. Geo. H. Bertram, M.P., is actively co-operating with the city authorities to obtain the necessary authority form the Dominion Government for the construction of the bridge.” Globe, March 8, 1898

“Free Bathing Popular. The popularity of the free swimming baths at Fisherman’s Island is evidently on the increase. Mr. Hector McDonell [sic], who has charge of the baths, reports that last week the number of boys availing themselves of the boon was but a few short of 5,000. The numbers for the six days were respectively 800, 816, 958, 817 and 760, a total of 4,981.” Globe, Aug 3, 1898

1899 “Death in the Storm. One Life Lost and Many Accidents in Saturday’s Tornado.”

William Scott drowned. Hot day. Thousands on the water. “In the twinkling of an eye a great rush of wind came from the southwest through the semi-darkness. The fury of it tore the canvas and spars from the small craft on the lake and the branches from trees of the land. Yachts and row-boats were capsized, the large ferries were driven out of their course and dared not try to make port, and the lake boats, loaded with passengers were brought to face the wind, stopped their engines and fought the storm until it spent its fury.” Winds were clocked at 40 mph. The Meteorological Observatory described at as a squall during a thunderstorm, not a tornado. Globe, July 31, 1899

1900 “Daring Cost His Life” Norman Rogers (8 years old) drowned on Fisherman’s Island’s beach. He was “on the first trip of the free ferry”. He was taken out into the lake by a “huge wave”. Robert C. Newman, in charge of the city swimming, and Hector McDonald who looked after the free baths at Fisherman’s Island tried to resuscitate him unsuccessfully. Globe, Aug 8, 1900

“Free Ferries Off.” The free ferries which carried boys to the swimming areas on “Sand Bar Point” and “Fisherman’s Island” stopped because the funding ran out. In July and August, 1900 117,600 used the swimming areas. However the boys could still reach the swimming areas by walking. Globe, Aug 28, 1900

1901 “Squatters on the Sandbar. Assessment Commissioner Fleming had before the Board of Control yesterday morning a report upon the occupation by summer squatters of the beach between Fisherman’s Island and Kew beach. he gave the names of 36 persons located there, all of them dating their location within three years, except three, one of whom claimed to have resided on the beach thirty years, and the others ten years. The Commissioner says: “These people are trespassers and have no authority to occupy said lands. They had no permit from this department to locate there. They are paying no rental, because this department declined to complicate matters by accepting rent from them. They are prepared to pay the usual charge for tenting privileges, $4 a year. As to who gave them permission to locate on the bar, I cannot say; the people state they received it from some of the members of Council.” Globe, Oct 16, 1901

1903 “Met Death in the Bay” Two men, believed to be Jewish rag and bone men (peddlers) drowned in the bay. “Hector McDonald of Fisherman’s Island was returning after setting his nets when he sailed close to them. He thought at the time they had too big a load, and feared that they would not reach the city in safety. Everything seemed to be packed in the bow. The load consisted of rags, bones and bottles, and Mr. McDonald concluded that the occupants of the boat were peddlers who had been to the Island picking up what they could find.” Globe, April 29, 1903

1904 Ice Boats Ice boating was popular on Toronto harbour. There were 17 in the commercial fleet and people enjoyed racing. “This year, in one of the fastest races ever sailed on Toronto Bay, the Volunteer, the latest addition to the fleet, and owned by Hector Macdonald of Fisherman’s Island, won the Rogers championship Cup.” Globe, April 5, 1904

Belonged to Owen Sound. Howard Douglas drowned. 19 years old. Hired a canoe with a friend. He stood up and the canoe overturned. James Ramsden (Fisherman’s Island) and another man rescued the companion, William Bell, but Douglas drowned. Globe, June 13, 1904

Lem [Len] and Harry Marsh, two residents of Fisherman’s Island, were convicted by Police Magistrate Denison yesterday on the charge of illegal fishing in Ashbridge’s Bay. They were each fined $30 and costs. [Almost a months’ wages.] Globe, June 17, 1904

On the suggestion of Mr. H. MacDonald an effort will be made to have a polling booth on Fisherman’s Island to accommodate the score or so of voters who remain there all the winter. Globe, Sept 20, 1904

On October 15 Charles Pickering wrote about sighting of three Canada Jays on Fisherman’s Island. He also saw snowbirds [Snow buntings]. On October 11th and October 12th flocks of geese were seen. Gray Jay, Fisherman’s Island Globe, Oct 19, 1904

Five men on Fisherman’s Island were rejected by the registrars of South Toronto. That part of the Island is in East Toronto in Provincial affairs. The appeals of the men were all allowed. Globe, Oct 26, 1904

The home of Mr. Frank Kerrison on Fisherman’s Island was practically destroyed by fire about noon on Saturday while the occupants were in the city shopping. The Bolton avenue section extinguished the flames. The loss on the house is estimated at $800, and on the contents $200. There is no insurance. Globe, Oct 31, 1904

Fire on Fisherman’s Island. About 2 o’clock yesterday morning William Ramsden’s summer cottage on Fisherman’s Island caught fire, and with his boathouse and workshop, was completely destroyed. The family were in bed when the house took fire, and do not know how it started. Mr. Ramsden’s house , with the outhouses and their contents, were valued at $3,000, and were insured for about one-third of their value. Globe, Dec 8, 1904

The fishing folk of Fisherman’s Island anchored their boats in the quiet waters of Ashbridges Bay on the north side of their island rather than in the rough waters of Lake Ontario to the south.

To Be Called St. Nicholas. St. Nicholas’ Anglican Church is the title of a new frame house of worship to be erected on Fisherman’s Island, on the site now used for the Sunday tent services on the lake shore near Simcoe park. The church is to be named after the patron saint of all sailors and fishermen. The clergy of St. James’ Cathedral have undertaken to hold divine service every Sunday afternoon at 3.30, to be preceded by a Sunday School.

A garden party and fish supper were given on Thursday evening by the island residents. The fish for the supper were provided by the fishermen of the island. An orchestra was in attendance, and there were the usual side entertainments, by which the ladies added to the treasury for the building. Globe, July 22, 1905

Reckless Shooting on Island. Mrs. B. Matthews of Coatsworth’s Cut brought an eleven months’ old baby to the City Hall yesterday. In the baby’s head were wounds made by birds shot, which were caused while the baby was in its mother’s arms. Mrs. Matthews, who was accompanied by Mrs. Thomas Smith of Fisherman’s Island, said that there were dozens of boys and young men with rifles at the Island, and lives were constantly in danger. If any residents complained the boys would take revenge by firing at the houses. The Board of Control yesterday deferred consideration of a bill to regulate shooting on the Island. Globe, Sept 20, 1905

Squatter’s Demands. The forty-five squatters on the sandbar east of Coatsworth’s Cut [Woodbine Beach], who have enjoyed freedom from the annoyances of leases or landlords, must now pay some rent to the city. Commissioner Forman has fixed a nominal rental for the land seized by the squatters for their little cottages, so that the city’s right of ownership might never be imperilled. He offered the squatters a five-year lease, and he reported to the Property Committee last week that ten of the squatters had accepted the new conditions and agreed to pay a rental of 40 cents a foot for five years. The other squatters, however, are looking for still more liberal terms, and a number of them came before the Board of Control. Globe, September 20, 1905

1906 Snowy owl on Fisherman’s Island. [First of many columns on birds and nature at Fisherman’s Island] “A few days ago a white owl came to grief on Fisherman’s Island, where guns are always ready and owls are outlaws.” A Lonesome Owl Fisherman’s Island Globe, February 17, 1906

1911 William McCurdy biplane from Hamilton to Toronto. Landed on the beach outside the Smith door. Smith family having a birthday party; McCurdy’s too – he joined the Smith’s party. McCurdy was due to appear on Aug. 3 for an air show at Donlands Farm. In a race with Willard. Thick haze, couldn’t land at Donlands Farm, so landed on Fisherman’s Island. Hilda Smith was surprised when a huge “lake bird” appeared and landed outside her house. McCurdy had the fastest time – he took the direct route over the lake; Willard followed the shore lines. Willard landed at the CNE grounds.

1912 Toronto Harbor Commission Plan published.

1916 THC Plan. Landfilling began 1916. Concrete harbor head wall between the Don and Bay Street, new southerly extension of Toronto shoreline. Dredging.

Smith’s forced to leave Fisherman’s Island because of THC development. Island was joined to the mainland with fill.

1920s By early 1920s cottages replaced many of the shacks and boathouses of the area’s largely summer (transient) residents. Late 1920s Woodbine Beach lands were expropriated and leases were allowed to lapse. All residents of Fisherman’s Island had their leases expropriated and cottages torn down or relocated. Coincided with THC lake filling operations and plans to industrialize Fisherman’s Island.

Leave a comment